Co-Authored by Education Alliance Coordinator David Lloyd.

When communities become silos

Communities coalesce around shared ideas, professions, hobbies, ages, religious beliefs or values. The communities can align along a variety of structures: geographically, institutionally and, in the 21st century, even virtually. More often than not, these communities benefit the people who are part of them and the broader world in which they live. An artists’ colony, for example allows artists to share resources, ideas and support to produce art enjoyed by the entire world.

In certain cases, these sub-communities become walled off from the larger community. Internal biases, misunderstandings with those not in the community, a disparity of resources and a host of other forces create silos around sub-communities that preclude interactions. Those barriers harm not only the individual community, but the world in which we all live.

But at the same time, the 21st century offers opportunities for unparalleled and unique connections across sub-communities that foster new ideas, opportunities and improvements that benefit broader environments.

In Central Texas, several silos are affecting the region’s educational achievement and, if not addressed, will limit our sustained success into the 21st century.

Austin Bridge Builders Alliance (ABBA) exists to build metaphorical bridges from Christian resources to needs found in the Greater Austin Area. It is comprised of churches, organizations, and individual Christian influencers. ABBA now taps the power of 21st century networking to improve education today by forging enduring connections between the education system and communities.

Walls around classrooms

In the past fifty years, education as a “system” has become highly specialized. As our understanding of learning and teaching as a science advances, we’ve ushered in the unintended consequence of dividing educators and communities. Teachers and school administrators are considered the experts on how to guide a child to educational success. Parents supported and relied on that. There was an assumption that if parents just dropped children off at school, the children would come out of the building with a complete set of skills to explore their world. Communities came to rely on that as well, holding schools responsible for producing successful students within their four walls.

The problem is not with the professionalization of education—indeed the understanding of how to educate children is extraordinary and has evolved tremendously. The problem is that faculties and administrators have been expected to do alone what only a community can do together.— Schools simply cannot be the only institutions invested in the successful development of students. No matter how capable a teacher, addressing core competencies is only one piece of cultivating a child and cannot be separated from the social, personal and community conditions in which that child exists.

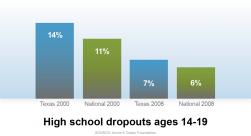

Yet even as we increase the attention and accountability for educational attainment, success has become more elusive at every level of society. Texas’ drop-out rates are higher than national averages. Children from all economic levels are struggling in college, needing remedial classes or failing to graduate. Parents seek outside tutoring and enrichment programs to ensure their children can pass standardized tests.

The consequences of these flawed assumptions can no longer be ignored as the United States competes on a global scale in a highly educated, knowledge-intensive world.

Divisions between communities

As different communities seek enrichment to pursue student success, additional silos developed. Upper class families left the public education system for private school programs that had the resources to cultivate every element of a child. Middle class families form parent associations to support the work of the teachers in the classroom—and then seek outside tutoring and education enrichment programs to fill the gaps the schools could not provide.

At the lower end of the financial spectrum, social programs developed to provide enrichment programs. But while there are many highly successful publicly-supported programs, they cannot be applied consistently to every child who needs it. And in lower-income neighborhoods in which parents might not have the same cultural connections to schools, those partnerships are tenuous at best.

The consequences of this divide are starkly apparent when we look at 3rd grade reading levels and drop-out rates. If a child has not mastered reading by the 3rd grade, he or she cannot keep up, let alone succeed in school, increasing the possibility of dropping out of high school. Illiteracy and dropout rates are demonstrably higher in low-income neighborhoods. And it’s a self-perpetuating barrier: parents who do not connect with school produce children who do not connect with school.

If we cannot break down those barriers, the 21st century will be defined by impenetrable economic, social and cultural divisions.

Breaking down walls

In the months following the Hurricane Katrina disaster in 2005, Christian churches across Austin forged partnerships to settle and heal refugees arriving in Austin. In coming together outside the four walls of our churches, we recognized the power of connections in solving the issues facing our community.

Following Hurricane Katrina, ABBA sought new opportunities to forge connections throughout Central Texas. In 2010, ABBA Pastors in Covenant convened a meeting with the school district superintendents from Austin, Pflugerville and Round Rock to understand their needs and how we could support their work to improve education for all Central Texas children.

We learned that the issues keeping children from learning were due to the barriers among communities and community relationships with schools—and stemmed from issues completely outside a schools’ control. Often the biggest hurdle is just getting a child out their front door in the morning and into the classroom. Alternatively, kids came from home environments couldn’t support a child’s ability to be in school—whether from hunger, anxiety over unstable housing, single-parent—or no-parent households.

ABBA saw this as an ideal opportunity to break down unnecessary walls between communities and open up avenues for the sharing of knowledge and time to improve results for all of Austin.

Building whole relationships

Six ABBA-affiliated congregations are currently establishing relationships with schools across Central Texas using the Kids Hope USA mentorship model. Congregations identify their pool of available talent and resources and receiving training from ABBA for the most effective ways to apply those resources to improve schools.

A relationship between a church and a school is entirely voluntary. Churches and schools identify the ways in which they intersect, based on the available tools and pressing needs. There are a range of ways they can potentially interact: Churches can provide services like cleaning up the playground, providing meals, or hosting celebrations for teachers and staff. Or they can have a more hands on relationship with children through tutoring and/or one-on-one mentoring. . In most cases these partnerships build slowly as both service-oriented institutions learn to work together. A partnership with mentoring involves the highest level of commitment from the church and trust from the school.

Long-term, we anticipate seeing measurable improvements in academic success, but our more immediate goal is seeing how many connections we can create that will advance our community holistically and positively. Our goal is to develop ongoing, dynamic relationships where we are learning from the school, ensuring parents and children receive the support they need, and seeing that in a united front our communities are invested in the success of our educational systems.