Kids who are in school now will, when they graduate, have to reach across continents to collaborate on solutions to energy problems, pollution and the dwindling water supply. They’ll have to work with teams of engineers, designers and marketers to develop products and bring them to market. They’ll need to relate to all kinds of people, adapt to cultural differences, think critically and solve complex problems.

But today’s schools often follow models from the 1950s. Kids sit in desks, answer questions and regurgitate information from lectures and reading assignments. Can that prepare them for the problems they will have to solve and the relationships they will need to forge?

Two Austin organizations have devised hands-on learning approaches to empower youth. Both Creative Action and EcoRiseYouth Innovations get kids physically involved in projects that teach them to use their voices, stand up for what they believe in, develop empathy for others’ perspectives and use critical thinking to solve problems.

![]()

Creative Action teaches students to play a courageous role

Creative Action teaches students to play a courageous role

Creative Action uses unique arts-based programming to empower young people to solve problems and resolve conflict. The group’s mission is to teach children to become creative artists, courageous allies, critical thinkers and confident leaders.

The organization has 55 teachers and 18 full-time staff members who provide more than 600 hours of in school, after school and community programming a week in school 7 districts as well as in low-income housing sites and juvenile detention centers.

“The pedagogy of our programming works off the premise that we provide opportunities, pose scenarios and ask questions,” Executive Director Karen LaShelle says. “We’re not providing them with answers but making them part of solving problems. We use inquiry and dialog as opposed to just delivering information.”

“The pedagogy of our programming works off the premise that we provide opportunities, pose scenarios and ask questions,” Executive Director Karen LaShelle says. “We’re not providing them with answers but making them part of solving problems. We use inquiry and dialog as opposed to just delivering information.”

Elementary students might watch a musical puppet show about a fight amongst Barton Creek animals. Creative Action teaching artists act out an imaginary world where animals teach the students a 4-step conflict resolution process that they can then impart to the Barton Creek animals.

Older children might discover how to be a courageous bystander — the one who stands up  when a bully is picking on another child. They encounter historical figures: those who protected African American children in Little Rock, Arkansas, during desegregation or Danish citizens who hid Jews from the Nazis. High school students can enlist to perform plays — for pay — on topics such as sexual harassment, bullying and homophobia.

when a bully is picking on another child. They encounter historical figures: those who protected African American children in Little Rock, Arkansas, during desegregation or Danish citizens who hid Jews from the Nazis. High school students can enlist to perform plays — for pay — on topics such as sexual harassment, bullying and homophobia.

Creative Action aims to engage students mentally, verbally and physically in a way that creates a new relationship with the issue.

“We teach them to take multiple perspectives to a problem, work with peers to come up with a solution or strategy,” LaShelle says “All the while they’re gaining confidence in their own ideas, their ability to make a change and their ability to be themselves.”

The organization has after-school programs as well where kids might produce a short film on a topic such as the environment. The students have to explore the issues, do the research and form an opinion that will inform the film — all of which teaches critical thinking.

The organization has after-school programs as well where kids might produce a short film on a topic such as the environment. The students have to explore the issues, do the research and form an opinion that will inform the film — all of which teaches critical thinking.

Instead of leaving children on their own, where the natural pecking order frequently determines who is in charge, the teachers ensure everyone’s ideas are heard.

“A basic concept of improvisation is the idea of ‘Yes, and?’” LaShelle says. “We try to create a culture where we say ‘Yes, and?’ building on one another’s ideas.”

So all of the kids, especially the ones who have trouble sitting in desks all day, get swept up in the project, she says. “One thing that’s really exciting is that you can just look at the kids’ eyes and you know right away they are listening and taking in and processing information in a very activated way.”

Get Involved with Creative Action

![]()

EcoRise Youth Innovations develops sustainability entrepreneurs

EcoRise Youth Innovations develops sustainability entrepreneurs

EcoRise Youth Innovations trains teachers and develops curriculum to help students solve sustainability problems. That might include improving the school’s recycling program, building an outdoor classroom, creating a water catchment system or devising green homes. But the coolest part is the process.

“My hope is to develop kids as creative problem solvers, leaders taking action in their community,” says Gina LaMotte, the Founder and Executive Director. “I am less concerned about inspiring students to become environmental activists than to give them the tools to effectively solve the problems they are most passionate about.”

“My hope is to develop kids as creative problem solvers, leaders taking action in their community,” says Gina LaMotte, the Founder and Executive Director. “I am less concerned about inspiring students to become environmental activists than to give them the tools to effectively solve the problems they are most passionate about.”

In typical classrooms, students may create theoretical solutions to problems. But EcoRise students often build their projects and have to negotiate real problems: selling the idea to stakeholders, creating reasonable budgets and using an interactive process until the project succeeds.

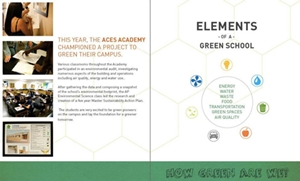

An EcoRise Youth Innovations Design Challenge begins by looking at a problem from multiple perspectives. Who are the stakeholders, and what are their preferences and biases? For example, Akins High School students conducted an ecological audit of the school. They considered what the school board might think about the costs of making the school more environmentally friendly and what problems they might have in contracting out the work. They considered whether faculty members would see the work as disruptive to the education process.

An EcoRise Youth Innovations Design Challenge begins by looking at a problem from multiple perspectives. Who are the stakeholders, and what are their preferences and biases? For example, Akins High School students conducted an ecological audit of the school. They considered what the school board might think about the costs of making the school more environmentally friendly and what problems they might have in contracting out the work. They considered whether faculty members would see the work as disruptive to the education process.

By looking at the world through stakeholders’ eyes, the students develop a sense of empathy and interconnectedness.

“Students must ask themselves: Yes, we are excited about this idea, but is it affordable? Is it viable? Will it be owned by the people we’re trying to serve?” LaMotte says.

Students then look at how the problem was solved historically and how it might be solved in the future. They also role-play. A child might be assigned the role of counselor, innovator, optimist or pessimist. After that, students brand their idea, develop infographics and public education campaigns, and write elevator pitches, manifestos and short business plans.

At Akins, students developed solutions that included installing sun shades on the windows, installing solar panels and switching all bulbs to T5 energy bulbs. They considered the cost, the work required, their enthusiasm level and who would have to do the work. They then mapped these factors to determine the viability of each idea.

And what would happen if the plan went out to the administration or school board and bombed? Not a problem, LaMotte says.

“They find out what’s working and what’s not working,” LaMotte says. “They make new prototypes and tweak things. They learn that if you haven’t developed empathy and understanding for those you are trying to serve, your product may not be successful. Then it’s all about trying again, testing, embracing failure.”

The program has benefits beyond training green designers and entrepreneurs, LaMotte says. Nearly all of the students adopt at least one sustainable living practice, and many become advocates for sustainability in their home. That teaches them to be leaders. Plus, a report by the North Carolina Environmental Education Office shows a connection between environmental literacy and increased test scores. And because energy is a huge cost for school districts, students taking charge of energy-saving projects could save the districts millions.

The program has benefits beyond training green designers and entrepreneurs, LaMotte says. Nearly all of the students adopt at least one sustainable living practice, and many become advocates for sustainability in their home. That teaches them to be leaders. Plus, a report by the North Carolina Environmental Education Office shows a connection between environmental literacy and increased test scores. And because energy is a huge cost for school districts, students taking charge of energy-saving projects could save the districts millions.

LaMotte’s vision is to someday train teachers around the world, working with them to develop curriculum that fit their cultures, and then connect Austin students with those in other nations to tackle projects as a global community.