Editor’s Note: Education is a critical element in helping individuals and families avoid or rise above poverty. Yet the very circumstances of poverty make it extremely challenging for children whose families have a tenuous grasp on housing to connect with the education infrastructure, let alone gain the tools they need for sustainable citizenship.

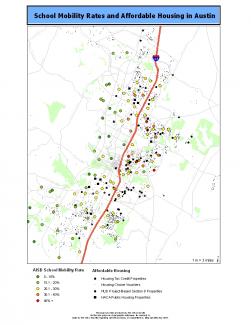

More than sixteen thousand children in the Austin Independent School District are classified as “highly mobile.” These are children who do not have stable and sustainable housing. In this interview, Forefront asks Cathy Requejo of AISD’s Project HELP and Nancy Maniscalco of Govalle Elementary School how fragile housing and the resulting mobility of children affects their ability to receive the education they need, the education all AISD students receive, and the overall health of the Austin education system.

Forefront (FF): What is student mobility?

Cathy Requejo (CR): The recent “Housing/Student Mobility White Paper” produced by the city of Austin defines mobility as “student turnover at a school during the academic year.” And we distinguish between strategic mobility, which is when a student changes schools due to the family’s upward mobility, and reactive mobility, when a student is forced to move due to residential instability.

FF: So strategic mobility is seen as positive, unlike reactive mobility. What are some of the leading causes of reactive mobility?

CR: Family issues are a big factor with reactively mobile students. Family crisis or struggles often result in and cause housing instability. Families move to chase free or reduced rent or double up with another household in temporary quarters. They struggle to pay high utility bills in poorly insulated houses and often face eviction, damaging their rental history and further limiting their housing choices.

And don’t forget that some of these students are parents, too. They move between family, friends, and shelters or try to make it on their own, often resulting in financial crisis.

FF: What impact does reactive mobility have on a student?

Nancy Maniscalco (NM): Many reactively mobile children end up with gaps in their education and, ultimately, disenfranchised from the education process. They experience academic and emotional instability, developing relationships with peers and teachers that end abruptly when they begin again in another school. It’s common for us to find that many of our highest-need students have attended as many as four schools within a single school year.

These students and their parents have little sense of belonging to an established learning community and, therefore, develop a diminished sense of accountability and expectations for academic success. All of this leads to issues with attendance, academic achievement, and trust.

CR: Reactively mobile students tend to be, on average, two years behind their peers academically and are at a higher risk of dropping out. A student who feels safe and stable will be more receptive to learning. Some children who move adapt well, but others become angry or withdrawn.

Students whose mobility issues cause them to fall behind become frustrated. They are depressed, come to school sleepy and hungry, and exhibit other behaviors that impede their success. Their situations frustrate their teachers, too, which can affect teacher morale, increase teacher turnover, and result in fewer qualified teachers working in schools with high student mobility.

FF: Reactive mobility clearly damages students’ educational opportunities, but what about the impact on their classrooms and peers?

NM: Reactively mobile students carry large amounts of social and emotional baggage. Those living in unpredictable circumstances may not be as invested as their peers are in meeting a school’s academic and behavioral expectations. They display passivity, which looks like apathy, or disruptive behaviors in an effort to seek attention.

Teachers must be equipped to understand and address the students’ issues without jeopardizing the academic needs of their classmates. School staff must support these students and their families with services and interventions. The entire staff in schools with a large percentage of highly mobile students requires specialized training in SEL (Social and Emotional Learning) and effective instructional delivery, and must have an especially high level of commitment to their entire class.

FF: How does a campus with highly mobile families look compared to one with a more stable student population?

NM: We find it more challenging to communicate regularly with mobile parents. These parents are less likely to participate in school events, visit their children at school, and attend parent-teacher conferences. Some of these parents don’t even have a working phone number.

The only time many of these parents visit school is when they register their children or when they pick them up after school. We’ve been surprised at how often these parents don’t know the name of their child’s teacher.

A very high percentage of families new to our school have moved in with other families at Section 8 apartments, and they register using a Declaration of Residence, since they do not have a lease or utility bill in their name. This is another communication barrier, as we often have to communicate with our new families through the family they’ve moved in with.

Because we have so many children living in unstable circumstances, our school days are unpredictable, and we must exercise creativity and flexibility in addressing these issues every day.

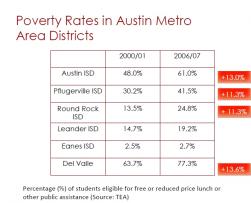

FF: Can reactive mobility affect an entire district?

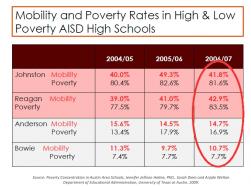

CR: Certainly. A high rate of school mobility is a stronger predictor of low ratings than school enrollment, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

We know that if students can attend one school for three consecutive years, their standardized test scores in all academic areas increase. Additionally, the school district loses funding through lost days of attendance. The district accountability ratings can drop because mobile students miss more school and, thus, have greater challenges passing state-mandated assessments.

FF: It seems like schools have two ways to reduce the problems associated with reactive mobility: help families gain stable housing, and serve highly mobile students. What is AISD doing in these areas?

CR: That’s an excellent observation. AISD offers several programs that cover both sides of that effort.

Project HELP (Homeless Education and Learning Program) gets highly mobile students to enroll, participate, and succeed in school by providing basic needs and academic services as well as linking students and families to AISD and community support services.

Austin Community Collaboration to Enhance Student Success (ACCESS) is an AISD-led community collaboration of public and nonprofit agencies working together to address the emotional, behavioral, and social needs of at-risk students. The program locates, targets, and serves those who experience the greatest needs.

AISD is also working with the Austin Housing Authority to provide aggregate reports on the attendance, discipline, and test scores of students who receive support services. These reports will assist the Housing Authority in identifying services.

The AISD Department of Learning Support Services has school-to-community liaisons who are assigned to high-need students. The counselors and social workers assist families by linking them with the appropriate social services.

And the AISD curriculum itself helps mobile students by maintaining consistent standards, scope, and sequence from campus to campus.

NM: As educators, we see the power of educating all of our students so that they can gain the tools they need to be good citizens. Our investments here pay dividends not only for these children and their families, but also for our greater community.