Editors Note: The Foster Angels of Central Texas Foundation is dedicated to improving the lives of children in foster care, ensuring that each child has his or her basic needs met, and providing children with life-enriching and life-enhancing experiences.

More than half a million children are in foster care in the United States, and 3,200 of those children live in Central Texas. A child in foster care has likely been removed from a home where he or she experienced poverty, abuse, and neglect.

Foster children are emancipated—or “age out”—of the foster system when they are eighteen. If a foster child ages out of foster care without a diploma and a stable, loving home, that child is almost guaranteed to repeat the cycle of poverty from which he or she came. Less than one in five foster children will be completely self-supporting four years after leaving the child welfare system. And one-fourth of all foster children will be homeless at least once.

In this article, Sarah Smith, the Executive Director of Foster Angels, and former CPS Caseworker Rebecca Rice discuss the cycle of poverty foster children can become trapped in and the important skills they need to be successful and independent as they age out of the foster system.

Sarah: Why are foster kids at such jeopardy of continuing the cycle of poverty?

Rebecca: First we need to consider the sense of rejection foster children face. Most are abused, neglected, and abandoned by the people who are supposed to love and protect them, their parents. More than one-third suffers emotional disturbances and the behavioral problems that often accompany them. Most of the children I work with have some sort of behavioral issue. They are understandably angry about their situation and have very few coping skills. When that trauma is not addressed, we often see aggressive or maladaptive behavior that only increases as the child gets older.

Sarah: And does getting into the foster system stop that rejection?

Rebecca: Unfortunately, the rejection cycle often continues as they move from home to home. It is incredibly rare for a child to be in one place for even two years. One child I worked with had eighteen placements in eighteen months. It is rare that a child is moved that often, but typically you would see a child being in four placements in twelve months.

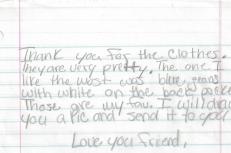

Every time a foster child moves, he or she faces a new school, new family, new pediatrician, new therapist, new home, and often a new caseworker. Frequently, when children are transferred to a new placement or home, everything they own is just put in a trash bag. That’s like telling them, “We’re throwing you out with the trash.”

Sarah: I think for most of us it is hard to even imagine having only one trash bag of personal belongings.

Rebecca: Foster children come from homes where they had very little of their own. A family of six siblings (ages one to nine years old) was found living in an abandoned church without running water or electricity. They came into foster care with the clothes they were wearing and nothing more; they didn’t even have shoes. I can remember how important it was to me to have name-brand jeans as a teenager. I have foster children who have maybe a couple sets of clothes that they wear to school every day.

Sarah: These are tremendous emotional challenges to overcome. But to be successful in adulthood, children also need to master some very basic skills. Let’s talk about the tools these children need now so that they can be successful when they “age out.”

Clearly, education is critical to breaking that cycle. But our foster children tend to fall way behind in school. Often when a foster child moves, he or she must start at a new school. When you change schools, you encounter a new curriculum, new styles of teaching, a new principal, and a new teacher.

Rebecca: Yes, every move equates to a six-month loss of school. That puts these children light years behind. When these children get behind in school, they wonder, “Why should I even try?” They start to fail classes, and soon they are beyond the age of eighteen and unable to see why they should stay in school. Children who are aging out often say they will just get their GED, but many do not.

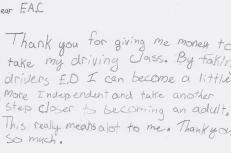

Yet, when foster children get the support and attention they need, they can astound you. I had one client who was in high school. She had fallen behind, but wanted to recover lost credits so that she can graduate in 2011. Foster Angels paid for this young woman’s summer school sessions to help her achieve her goal.

Another client is an eighteen-year-old who has been in permanent foster care in Travis County since he was just six years old. His mother severely abused and neglected him until he was removed from her care. He worked incredibly hard and did graduate from high school. That diploma was a huge personal accomplishment because he is the first person in his family to ever graduate from high school. Foster Angels was able to pay for his high school class ring of 2010.

Sarah: I think it is important to note that as these children age out, they do not necessarily have to go a traditional college. Associate degrees, technical schools, and training can make a big difference. These kids can often do very well if they pursue training at for example, cosmetology school.

Rebecca: Definitely. On the other hand, the alternatives if foster children do not do well and finish school are quite grim. Forty-six percent lack a high school diploma four years after leaving foster care. One of my clients said he would “throw dice,” a street gambling game, in order to get by. Many will head toward gang life or crime or find a way to make money outside of the system. Girls will often find boyfriends to live with, but too often the boyfriends are involved in crime or the girls become pregnant without means or skills to care for children, putting them right back in a potential cycle of abuse.

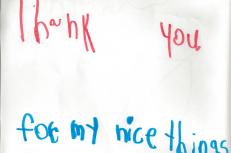

Sarah: In addition to support for studies, it is really important that children participate in some kind of activity, club, or sport. The experience of being in a regular activity teaches camaraderie, discipline, time management, responsibility, and commitment, among other things. Not to mention it is fun!

Rebecca: Absolutely. When a foster child has been let down by nearly every person in his or her life, being able to be a part of something is a wonderful thing. An activity can teach children critical skills that they will need as they age out of the foster care system. Children learn the importance of working as a team—they learn that you need to show up and be on time because people are counting on you. They learn that they can be successful.

Often, my clients cannot even fathom attempting to join a group or play a sport because they are worried about the costs involved and transportation needs. One client told me she wanted to join a group but that “it costs money,” so she cannot join. I asked her, “How much money?” Fifteen dollars.

Sarah: We had a seventeen-year-old foster child who worked incredibly hard to try out and make the cheerleading squad in high school. She made friends, was gaining self-esteem, and had a number of very positive relationships through cheerleading. Her caseworker came to us and said she wouldn’t be able to afford the fees—about $250—to participate. Foster Angels was able to pay those fees. On top of being able to help her financially, it is really thrilling to hear that she hopes cheerleading will help her get into college!

Let’s say a foster child has graduated from high school and been able to participate in a club or a sport. That is not the complete recipe for success as an adult. What is missing?

Rebecca: Foster children need major job-seeking and interviewing skills. They do not know how to go about looking for a job. The application process can be very overwhelming. They need help learning how to interview, how to shake hands, and why it is important to look people in the eye.

Sarah: Every child deserves to be safe and happy. Period. Foster Angels is dedicated to the well-being of kids in Austin, and because of that, we make sure that 100 percent of every dollar donated goes directly to the children. We are here to stay, and we are not going to give up on these kids.

Rebecca: Every Central Texan is impacted by the lives of our foster children as they become adults and either contribute to society, or rely on society. It is not impossible to break out of the cycle of poverty, but just like any child, a foster child needs tremendous support and tools to start a cycle of success.